I Let AI Agents Train Their Own Models. Here's What Actually Happened.

Two frontier agents, a pile of bugs, and a reality check on the future of autonomous AI research.

TL;DR: I built a system called Tinkerer that lets frontier AI agents (Claude Code, OpenAI Codex) autonomously fine-tune language models — no human in the loop. After 100+ experiments, the best run produced near-perfect arithmetic from a 3B model. The worst runs burned 10+ hours of compute because neither agent noticed a broken learning rate scheduler. My main takeaway: these agents can execute training pipelines, but they can't yet do ML research. Training is execution. Research is judgment. They're good at the first, still developing the second.

The Future Everyone Is Talking About

There is a narrative building in AI right now that feels almost inevitable: AI systems will soon train themselves.

At the World Economic Forum in January 2026, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei described the idea plainly:

"The mechanism whereby I imagined it would happen, is that we would make models that were good at coding and good at AI research, and we would use that to produce the next generational model and speed it up to create a loop that would increase the speed of model development."

He's not alone. In October 2025, Sam Altman laid out concrete internal milestones: "an automated AI research intern by September of 2026 running on hundreds of thousands of GPUs, and a true automated AI researcher by March of 2028."

Early results back this up. Sakana AI's "AI Scientist v2" had an AI-generated paper pass peer review at an ICLR 2025 workshop. DeepMind's AlphaEvolve uses an ensemble of Gemini models to discover algorithms that outperform decades of human research.

I built a system to test how close we actually are. After hundreds of training runs, I came away with a more nuanced view: we are closer than the skeptics think, but further than the hype suggests.

The Idea: Prompt-to-Train

What if anyone — not just ML engineers with years of experience — could describe what they want a model to do, and an AI agent would handle the rest? Generate the data, write the reward function, pick the hyperparameters, run the training loop, evaluate the results, iterate, and deliver a fine-tuned model.

I called the project Tinkerer. Three enabling technologies had just converged:

-

Tinker API (by Thinking Machines Lab) — a cloud fine-tuning service that exposes training as simple API calls:

sample(),forward_backward(),optim_step(). No GPUs needed on your end. An AI agent that can write Python can call these functions. -

Agentic coding tools (Claude Code with Opus 4.6, OpenAI Codex with GPT-5.2; sorry, 5.3 was not available on API at the time of writing) — capable of sustained, multi-step autonomous work: reading docs, writing code, calling tools, debugging errors, and iterating.

-

Model Context Protocol (MCP) — Anthropic's standard for connecting AI agents to external tools. This let me wrap Tinker's training primitives as MCP tools that any agent could call.

The setup: you run a single command, a Modal container spins up, an AI agent starts, it connects to Tinker via MCP, and it autonomously trains a model. You watch.

The first version was too ambitious — I gave the agents almost no tools and asked them to figure everything out. The gap between "can write plausible-looking ML code" and "can make good training decisions" was larger than I expected. So I narrowed the scope: a custom MCP server with exactly 8 well-designed tools, access to HuggingFace's dataset pool, and a playbook explaining the mental models behind GRPO (a reinforcement learning method where the model improves by comparing its own outputs against each other) and SFT (supervised fine-tuning on curated examples).

I ran both agents across 100+ experiments, tackling arithmetic on Llama-3.2-3B using GRPO and instruction-following on Qwen3-8B-Base using SFT.

Notable Runs

The Failure Mode Nobody Caught

Early on, multiple runs across both agents produced zero improvement. Dozens of gradient steps, over 10 hours of compute, completely flat reward curves. The culprit turned out to be a cosine learning rate scheduler (which gradually reduces the learning rate over time) that decayed to zero after just a few steps because of how the agent was calling the training API iteratively.

Neither agent noticed. Neither thought to check whether the learning rate was actually being applied. A human ML engineer would have caught this after two flat iterations. The agents just kept going.

With a bit more guidance and prompting, they picked up on it relatively quickly. But the fact that it went undetected for hours across multiple independent runs says something important: these agents execute procedures well, but they don't yet reason about why things aren't working.

Claude Code's Best Run

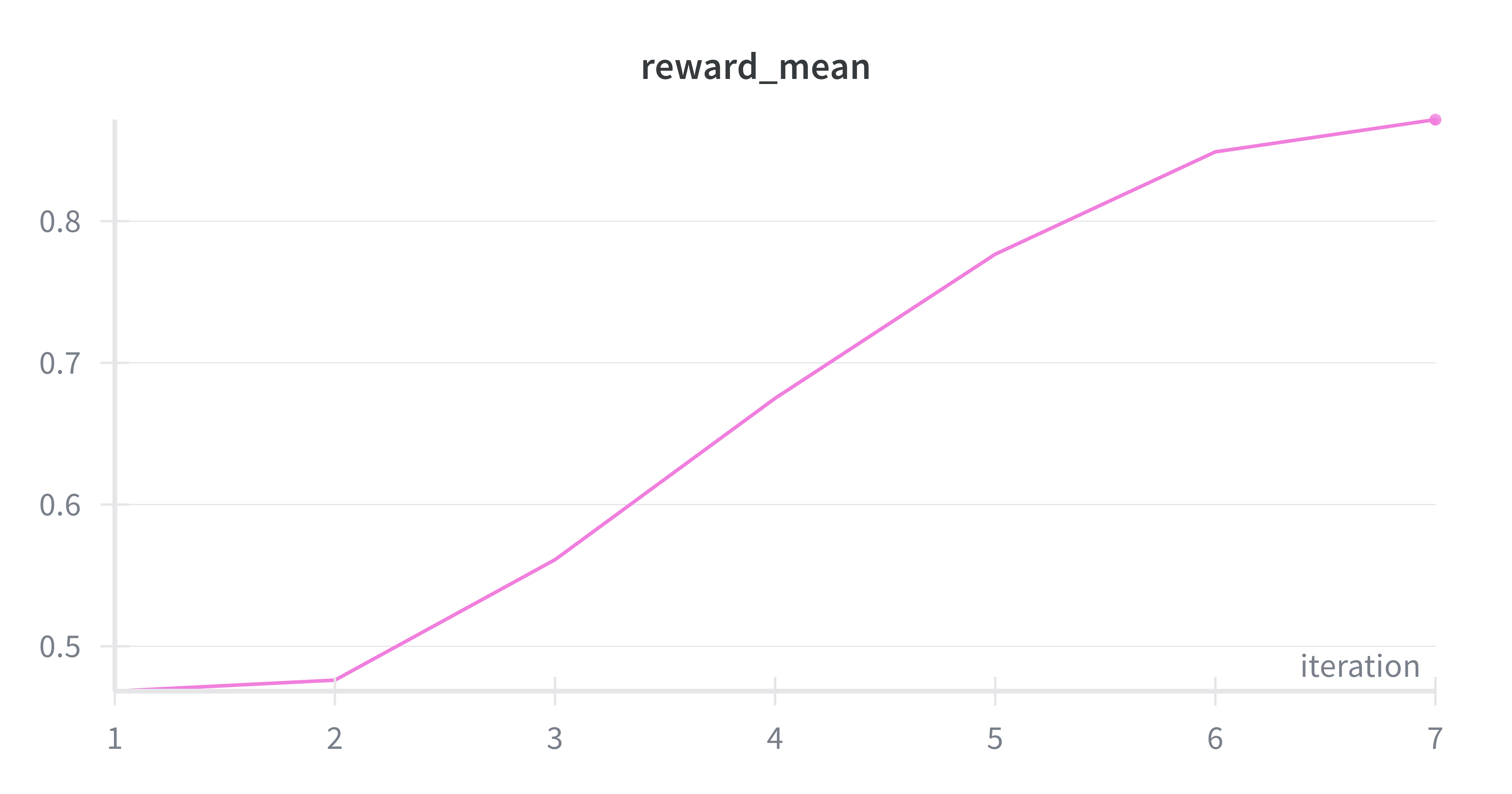

I gave Claude Code the ambiguous task of training the smallest model it could find on Tinker to learn arithmetic. It picked GRPO, generated 150 arithmetic problems per step, chose a sensible learning rate, and ran 6 clean iterations. Reward climbed from 0.60 to 0.95 in 18 minutes.

Then, without being asked, it tested the model on problems it had never seen during training: 123 + 456 = 579 (correct), 99 * 7 = 693 (correct), 18 * 12 = 216 (correct). The model had actually learned arithmetic, not just memorized the training set. Total cost: $0.90.

$0.90 in API costs. 18 minutes. Near-perfect arithmetic from a 3B model.

$0.90 in API costs. 18 minutes. Near-perfect arithmetic from a 3B model.

Self-Designed Curriculum for Harder Tasks

For a harder experiment with 3-digit arithmetic, Claude Code designed its own progressive difficulty curriculum — single-digit up through three-digit multiplication — and wrote a partial-credit reward function. Nobody told it to do either of these things.

The model scored 7/8 on out-of-distribution evaluation, correctly computing things like 35 * 42 = 1,470. The one failure was negative numbers: it output 5 for 3 - 8 instead of -5. A human would spot this as a training data distribution issue (most problems had positive results), but the agent didn't make that connection.

3-digit arithmetic with progressive difficulty. S-curve learning dynamics.

3-digit arithmetic with progressive difficulty. S-curve learning dynamics.

Comparing Claude Code and Codex

Both agents received identical system prompts, the same MCP tools, the same playbook, and the same task descriptions. The differences that emerged were purely behavioral.

Default Choices and Adaptability

Claude Code showed strong intuition from the start. Across every GRPO experiment, it chose a learning rate of 4e-5 without any prior feedback telling it this was right. It consistently picked LoRA rank 32 (a parameter that controls how much of the model gets updated during training), used 150-180 prompts per training step, and when both agents were independently asked to teach Qwen3-8B-Base instruction-following via SFT, Claude pulled 2,000 examples with a batch size of 128.

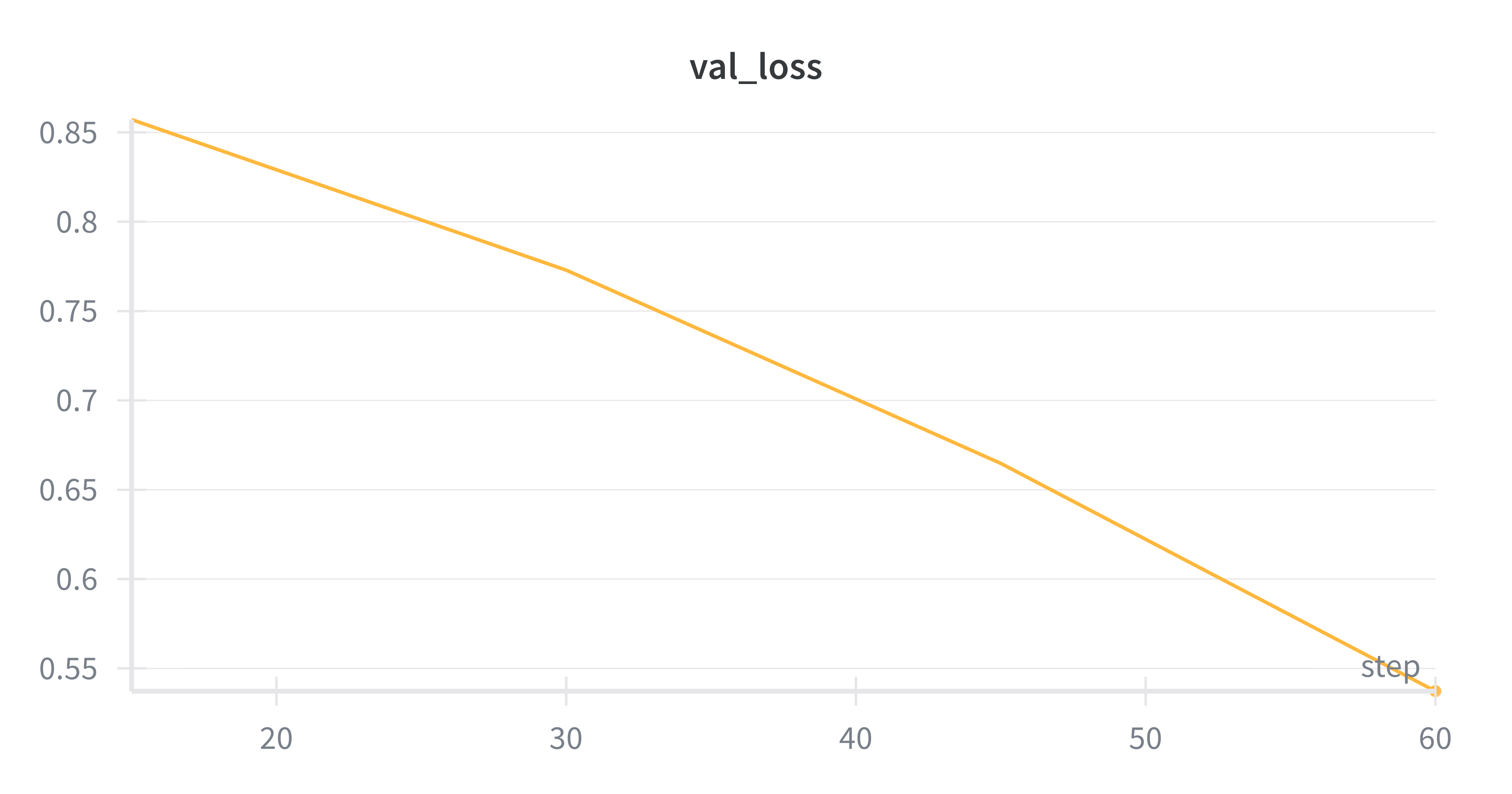

Codex's choices were less calibrated. Learning rates varied from 5e-6 to 1e-4 across runs, sometimes 4-8x below optimal. For the same SFT task, it pulled 300 examples with a batch size of 4. The loss curves illustrate the difference:

Claude: 2,000 examples, batch size 128. Validation loss drops from 0.86 to 0.54.

Claude: 2,000 examples, batch size 128. Validation loss drops from 0.86 to 0.54.

Codex: 300 examples, batch size 4. Same model, same goal — validation loss barely moves.

Codex: 300 examples, batch size 4. Same model, same goal — validation loss barely moves.

When things went wrong, the gap widened. Claude held its configuration steady and let the optimizer work. Codex would start changing things: new data, doubled learning rate, rewritten reward function. In one run, it used 7 different data subsets across 7 iterations. Changing the reward function mid-training in GRPO is particularly destructive — it effectively resets the model's progress — and the playbook warned against it. Claude never did it. Codex did it up to three times in a single run.

Unprompted Problem-Solving

Both agents occasionally showed intuition that went beyond the playbook. Claude independently tested its models on out-of-distribution problems after successful runs, and designed the progressive difficulty curriculum I mentioned earlier.

Codex had its moments too. In one under-performing run, it noticed the model was producing degenerate outputs (echoing the question instead of answering) and independently added "Answer with just the number" to the prompt. The skip rate dropped from 12.5% to 3.1% immediately. That's good diagnostic thinking.

The difference is consistency. Claude showed this kind of thinking in nearly every experiment. Codex showed it in isolated moments, often in the same run where it was also making counterproductive decisions elsewhere.

Summary

The difference between the two agents is judgment, not capability. Both can write code, call tools, and follow a training protocol. Claude Code behaves like a careful senior engineer who has internalized best practices. Codex behaves more like a talented junior researcher — good ideas, inconsistent execution. To Codex's credit, GPT-5.3 was meaningfully better in coding tasks than its predecessor, but as of the time of writing, it is not available on the API. Excited to try it out when it is.

Takeaways

With the right scaffolding, frontier AI agents can run complete training pipelines autonomously. They generate data, write reward functions, pick hyperparameters, iterate on metrics, and produce models that genuinely improve. The cost is negligible: the best runs were under a dollar.

Where they fall short is in the kind of reasoning that separates executing a training run from doing research. They don't notice when something is fundamentally broken. They don't make good stopping decisions. They don't learn from previous experiments — each run starts from scratch with no memory of what worked before.

Training a model and doing ML research are different tasks. Training is execution. Research is judgment. These agents are good at the first and still developing the second.

The AI-trains-AI loop is not a fantasy — it works on constrained tasks today. But the gap between that and independently advancing ML research is significant, and it's not obvious that it closes through scaling alone.

Tinkerer gives a generally capable agent the right tools, data, and instructions to do a specific professional task. The agent executes a research protocol that a human designed. It's getting better with each model generation, and it's a meaningful step toward more autonomous AI research. But it's a step, not the finish line.

Tinkerer is open-source. Explore the code, run your own experiments, and see what happens when you let AI agents train models: github.com/Hamza-Mos/tinkerer

Built with Tinker API by Thinking Machines Lab, Claude Code by Anthropic, Codex by OpenAI, and Modal for cloud infrastructure.